Title: Making it up – ‘Impermanence and Mortality’

Demonstration of technical and visual skills

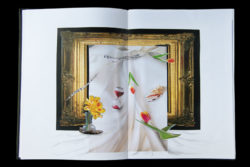

The whole process of developing ‘Impermanence and Mortality’ has served to develop my technical skills. It has pushed my still life skills in terms of taking each of the shots (at least ten individual shoots make up each image) and having to consider angle, lighting and depth of field to ensure they would fit within the overall composite. In creating the final images I had to focus on composition and balance, thinking carefully about where I placed each object, colour combinations and so on. It has also developed my Photoshop skills much further than I could have imagined – using the pen tool for cutting out (instead of quick selection), blurring borders slightly so the overlay is more effective, creating shadows with the burn tool and brush and so on. Having a clear sense of what I wanted to achieve as a result of the development process really helped ensure my technical skills were used appropriately. It definitely feels like a case of practice, practice and more practice!

Quality of outcome

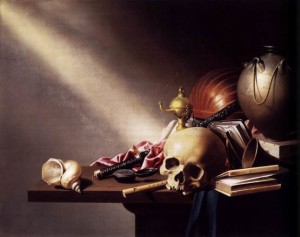

I think the research process really helped me achieve the best outcome I could. Looking at some of the Vanitas paintings and becoming more familiar with the original symbolism helped me in relating that to a contemporary context. I am particularly pleased with the development from the early sketches that were little more than copying the genre to something that feels much more like my own distinctive approach. Feedback from other OCA students through Facebook seems to suggest that the conceptualisation of the ideas worked for them – they mentioned being drawn in by the images and wanting to know more, feeling I had met my intention, that the images were strong and that the Vanitas symbolism worked well. They also offered advice on areas for improvement.

Demonstration of creativity

I feel that of all my Context and Narrative assignments this is the most creative. In my view it has built on the previous submissions but then takes the approach to a new level. I was concerned that I didn’t have the skills to achieve what I had in my mind’s eye but I think by building on each stage in the development process I was able to grow my confidence and move towards the images I wanted. This was helped by feedback from the Thames Valley Photography Group who asked some very helpful questions after I had completed the earlier sketches. It was this feedback that led me to think of the series of three. Each stage in the process helped push my imagination and I had not come across a concept like this anywhere else, although it is sometimes hard when you are working on your own because I wasn’t sure if I was straying too far from the brief. This is partly why I sought out other feedback to see what meaning others might take from the series.

Context

This assignment is the result of dedicated reflection and research. It involved a lot of thinking about my own mortality and was personally quite challenging particularly as I have lost many close relatives in recent years and in the week I was finalising the images I got the news that a friend who is two years younger than me had died of Leukemia. It was actually Mother Earth I found hardest because it was difficult not to feel a sense of hopelessness, it was partly why I wanted to create something that I hoped looked quite beautiful but when you look closely there is an inherent ugliness.

In terms of critical thinking a number of themes and emotions surfaced during this assignment, all of which could lead me to further research and development:

- Humankind’s relationship to materiality, consumption and possessions

- The potential for objects to instill a sense of melancholy

- Interest in the proposition that still life as a genre is under theorised

- Anger about the gender gap that appears steadfast in the arts

- Anger and sadness about our arrogance as a species

As shown in my learning log my research took me from Roman mosaics to the work of Olivia Parker and many in between. I spent some time researching the Vanitas still life tradition, which is what led me to the women artists of the period. As usual I continued to use my Pinterest Boards (Still Life, Still Life Photography, Impermanence) to collect examples and really expanded the use of my sketchbook during this period.