Assignment Four: Write an essay of 1,000 words on an image of your choice. The image I have selected is The Cut by Dara Scully, 2015

The Cut, Dara Scully, 2015

On the wall to the left of my computer is a black and white photograph; a young girl stares back at me uncompromisingly. Having considered several photographs (see my learning log) this was the image I kept returning to. There were occasions I looked at ‘The Cut’ and I imagined seeing my younger self looking back. The signification that emerged for me is that of belligerence. I could almost hear my mother’s voice – ‘don’t you dare, don’t you cut that plait!’ At which point I would hear the clip of the blades and the braid would be limp in my hand. My parents would have described me as a wilful child. I have interpreted the gesture as an act of asserting identity and autonomy. Given the polysemous (Barthes, 1977) nature of photography this personal response sets the context for my interpretation and analysis of the photograph.

Dara Scully (b.1989) is a photographer and writer based in Spain. She studied Fine Arts at Salamanca University and has a wonderfully lyrical way of describing her practice. She accepts she is obsessed with childhood, ‘maybe it’s because everything is so pure in childhood, so raw…cruelty, tenderness, evil, kindness… they feel all those feelings and show us just as they are.’(Ashley, 2015b)

She has exhibited in Spain and internationally, and was ‘Commended’ this year in the Sony World Photography Awards (People Category). While she is attracting growing acclaim for her work she has also been subject to some critique for her explorations of childhood (not unlike Sally Mann) and death. This posed a question for me around accepted portrayals of children and childhood.

A while back I featured an image of Dara Scully’s on the Instagram feed and immediately it drew a lot of attention; a few were disgusted by her work while others defended it…I embrace the fact that some of the images make the viewer a bit uncomfortable.(Ashley, 2015a)

At first glance the image may appear to denote a candid moment of a child playing. A neatly dressed young girl (perhaps in school uniform) looks to camera, behind her the background foliage is out of focus, the shallow depth of field making her all the more pronounced. Her hair is a little tussled and the parting is crooked but the plait looks neatly braided. You then notice her gaze and the claw like fingers on the scissors that are poised across the plait. Her right hand (almost out of shot) is holding the hair firmly. The black and white nature of the image and the clothes she is wearing give the photograph an ambiguous position in time, it could be contemporary or it could be historical. The Cut’s connotations for me echo myths and fairy tales; those dark tales of childhood, often in woods or forests, where good battles evil.

The studium appears to speak of childhood and possibly coming of age, whereas, the punctum is the scissors and the nature of her gaze. These signs are ‘that accident which pricks me.’ (Barthes, 1981: 27) This is not a passive, acquiescent, childlike look. It has a darkness to it. She looks defiant with wisdom beyond her years. Almost daring the photographer to take a step closer (or maybe even to take the photograph?) and if she does she will sever the plait. There is something threatening in her stance and her gaze.

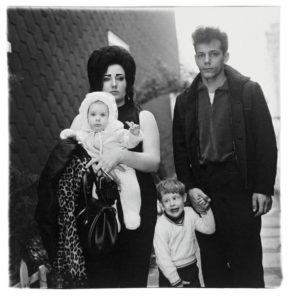

In exploring the intertextuality of ‘The Cut’ I am reminded of the iconic coming of age work of Szabo, particularly ‘Priscilla’, here the plait and scissors are replaced by the cigarette, but the defiance in the gaze is similar. There are also echoes in ‘Long Island Girl’ and Sally Mann’s ‘Candy Cigarette’.

- Priscilla, Joseph Szabo, 1969

- Long Island Girl, Joseph Szabo,1974

- Candy Cigarette, Sally Mann, 1989

Szabo’s images recognise the often hidden complexities of the journey into adulthood too.

The innocence of the students can really affect you…a number of [my] images express the inner life, the inner difficulties that teenagers have. (Philips, 2014)

Perhaps, more interesting than the similarities are the contrasts to those images of a more romanticised ‘innocent’ childhood like those of Julia Margaret Cameron, and commercial advertising, which appear to have gained such a dominant place in the collective psyche.

- English Blossoms, Julia Margaret Cameron, 1873

- Hoyts Cologne advertisement. USA, 1890

- Shirley Temple, 1936

- Carters Sleepwear advertisment, 1980

Scully’s work feels brave, honest and revealing against this backdrop and in an era when there is so much concern about the representations of children. We endure news coverage of out of focus children and hear of schools banning parents photographing events. There is no doubt that safeguarding issues are important and I confess I was mindful of researching this issue. The Cut surfaces an important dialogue about our social concerns for the loss of innocence. It is suggested this is a largely adultcentric concern with the meanings of ‘childhood’ being largely determined and defined by adults for adults.(Robinson, 2008)

Thus, the defining boundary between adults and children, and the ultimate signifier of the child—childhood innocence—is a constructed social and moral concept. (Robinson, 2008: 115)

In this photograph I see Scully playing with this boundary and deliberately disrupting our conceptions of innocence and evil, childhood and adulthood. She does not do this lightly and the children she works with are active participants in her work, she recognises the delicate ground she is treading, ‘childhood and death are kind of taboo.’ (Ashley, 2015b) There is a perceived crisis in the apparent loss of an innocent childhood but it could be argued that this is actually more of a crisis of adulthood in a rapidly changing world.(Holland, 2004) In The Cut the gaze is confrontational a possible challenge to an established but diminishing power order. It opens a discourse that explores a more contested view of representations of childhood. The Cut, for me personally, recalls those periods of confusion, some darker days, in the twilight period of childhood and adulthood when the rules were unclear and I was grappling with being ‘me.’

Yet the bitter experience of being a child is very often a continuous struggle to escape from childhood, to leave behind precisely those qualities of simplicity, ignorance and innocence that are so highly valued. (Holland, 2004: 205)

Word count: 1,009

References and citations

ASHLEY. 2015a. Dara Scully on childhood unplugged. The Stork and the Beanstalk [Online]. Available from: http://www.thestorkandthebeanstalk.com/2015/10/02/dara-scully-on-childhood-unplugged/ [Accessed 18th March 2016 2016].

ASHLEY, J. 2015b. Childhood Unplugged features Dara Scully. Childhood Unplugged [Online]. Available from: https://childhoodunplugged.com/2015/10/02/childhood-unplugged-features-dara-scully/ [Accessed 4th March 2016 2016].

BARTHES, R. 1977. Rhetoric of the Image. In: HEATH, S. (ed.) Image Music Text. London: Harper Collins Publishers.

BARTHES, R. 1981. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard, New York, Hill and Wang.

HOLLAND, P. 2004. Picturing Childhood: The myth of the child in popular imagery, London, I.B.Taurus.

PHILIPS, A. 2014. In-between days: Joseph Szabo. Hunger TV [Online]. Available from: http://www.hungertv.com/photography/feature/in-between-days/ [Accessed 25th March 2016 2016].

ROBINSON, K., H 2008. In the name of ‘childhood innocence’: a discursive exploration of the moral panic associated with childhood and sexuality. Cultural studies Review, 14, 113-129.